Speculation

Farmers have sold their food grains in markets for millennia. For almost as long, traders, bankers, and moneylenders have been involved in financing and shaping those markets. Over time, financial players have tried to control those markets so as to pay the farmer less, or to charge the consumer more. The oldest market regulations in the world were created to protect farmers and consumers from such “cornered” markets. In recent decades, U.S. government regulation of many agricultural markets was severely weakened for long periods of time, clearing the way for speculators and grain traders to make the markets more volatile and to capture windfall profits.

Read More

In the United States today, the prices for commodity food grains such as wheat, corn, and soybeans are established in specialized markets such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange or the Kansas City Board of Trade (which was bought by CME in 2012). In these markets, farmers, traders, and other middlemen buy and sell the actual or physical grains. They also buy and sell various forms of “futures” contracts that commit the farmer and trader to deliver or accept a particular amount of physical grain at some particular moment for a particular price, at a date sometimes long in the future.

Futures contracts are designed to stabilize markets and the production and distribution of food grains. They serve as a way for farmers, traders, and food processors to protect themselves—or “hedge”—against sudden spikes or plunges in prices, as well as against pests, flooding, and other vagaries particular to agriculture. They do so by enabling traders to lend to farmers the money they require to plant, harvest, and deliver their crops. Futures allow both the farmer and buyer to plan ahead and to manage their businesses more effectively.

Futures contracts date back as far as 17th century Japan. In the United States, the Chicago Board of Trade established the first commodity futures market in 1864. Futures markets have been federally regulated since 1922. In today’s world, where grain trading is international in scope, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission regulate U.S. grain markets.

Despite the immense size of these markets, and despite the numerous regulatory checks, well-capitalized traders over the last two decades have found ways both to destabilize and to corner these markets. More volatile markets serve the trader by increasing the number of trades that take place each day, which in turn increases the fees that traders collect and the number of hedges they can sell. Cornering markets can enable traders and other speculators to sell both the physical grains and futures contracts for much higher prices.

The greater volatility in today’s markets is largely a function of the deregulation of commodity markets between the 1980s and the early 2000s. For most of the 20th Century, the U.S. government carefully regulated commodity markets. Key pieces of federal legislation, including the Grain Futures Act of 1922 and the US Commodity Exchange Act of 1936, empowered regulators to closely limit the participation of those traders, such as speculators and banks, who do not deal with the physical commodity. The Commodity Exchange Act also empowered regulators to set position limits, a ceiling on how many futures contracts a single investor can hold.

But beginning in the 1980s Congress and the Executive, under both Republican and Democratic control, relaxed the restrictions on non-commercial traders and position limits. They also allowed more trades to occur outside of the marketplace, in unregulated venues. One of the main outcomes of these changes was to make it possible for Wall Street traders to use commodity crops as investment tools.

Beginning in the 1990s, many futures markets for food grains – as well as for commodities like energy and metals – were flooded with money from investment firms that had until then played a small role in the agricultural supply chain. This flood was facilitated by the creation of the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index, which allowed bankers and traders to make money off commodities markets without absorbing much of the risk associated with such trading. Several other such commodity indexes followed. By the late 2000s, hundreds of billions of dollars had been invested in these new commodity indexes. Between 2006 and 2010, financial speculators held 70% of the Chicago Board of Trade’s wheat contracts.

The huge leap in trading from speculators contributed to a boom in commodity prices. Between January 2005 and March 2008, the value of commodity futures contracts controlled by investors doubled to around $400 billion. In 2008, grocery prices in the U.S. shot up 6.6%, the biggest spike since the oil crisis of 1980. The price of a bushel of wheat, which had held at $3 for years, hit nearly $13. Internationally, the average price of food, including commodities like soy, rice, and wheat, rose 80%. Unrest and riots related to high food prices broke out in several countries, including Egypt, Pakistan, and Indonesia.

Other factors played a role in the rising cost of food. Rapidly growing demand in China for livestock, which tend to eat a lot of grain, contributed to the price increases. Droughts in Australia and California devastated wheat and rice crops. But many analysts agree that speculation contributed greatly to the rising prices. In a 2010 report, Olivier De Schutter, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, stated that “a significant portion of the increases in price and volatility of essential food commodities [during the 2008 crisis] can only be explained by the emergence of a speculative bubble.”

In 2013, the Financial Times reported that the top 20 traders had made over $250 billion from commodities trading in the prior decade. The top four traders in profits were Mitsubishi, Glencore, Mitsui, and Cargill. Since the financial crisis of 2008 and greater scrutiny of bank speculation in commodities markets, players like Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have scaled back on their commodities holdings.

The four largest grain companies – Archer-Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus – have extensive operations on the commodity exchanges. Some of these companies and others have been found to use the information they glean from their wide-reaching commodity-handling operations to inform their commodity hedging strategies. The European Union has taken steps to limit or even criminalize such use of private information in commodity market trades. The exchanges themselves have also become more concentrated. For instance, the CME Group controls the Chicago Board of Trade, New York Mercantile Exchange, and Kansas City Board of Trade.

Since the beginning of the financial crisis, attempts have been made in the U.S. to rein in the power of hedge funds and investment banks in commodity market trading. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 included rulemaking that instituted stronger position limits for 28 commodities. But in 2016, top advisors at the CFTC challenged the necessity of such limits.

Between 2009 and 2014, under the leadership of Gary Gensler, the CFTC overhauled its oversight of derivatives markets. During that time period, the agency brought high profile cases against Barclays, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, UBS, and Goldman Sachs, some of which involved commodity speculation. The resulting fines levied against those companies were among the highest in the agency’s history.

Beer

In some respects, America’s market for beer has never looked healthier. Where fewer than a hundred brewers operated a generation ago, we now can count over 7,400 breweries, double the number there were just five years ago. Yet the market below this drinker’s paradise has, in certain respects, never been more closed. Two giant firms—Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI) and MillerCoors—now control some 60% of the US beer market. ABI alone sold about 39% of the beers in the U.S. in 2020, and 1 in every 5 beers on the planet. And ABI is working hard to further solidify that control. Over the last several years, the behemoth has purchased several craft breweries, including Chicago’s Goose Island and Seattle’s Elysium, seeking a greater stake in that expanding sector. And in November 2015, ABI reached an agreement to acquire SABMiller for $106 billion. That created a company that sells 30% of all the beers on the planet.

Read More

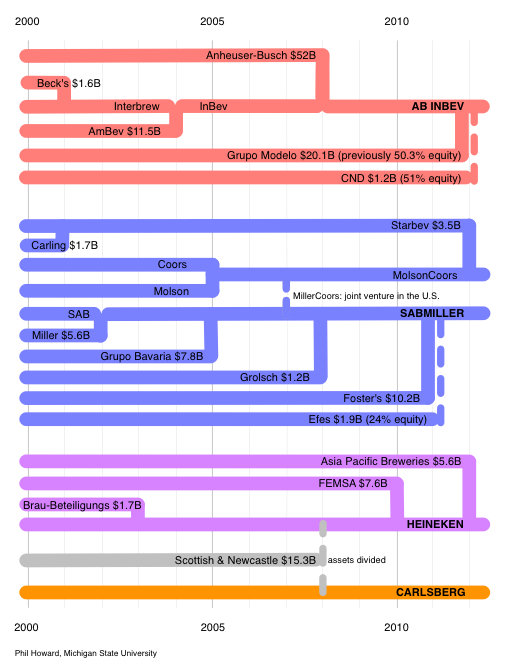

This chart from Michigan State University’s Phil Howard shows how concentration has taken hold of the beer industry in the past 15 years:

Just a few power players didn’t always dominate the beer industry. Almost 80 years ago, after the grand failure of Prohibition, Americans designed the “three-tier” system, a practical way to regulate the sale and consumption of alcohol. This system separated the activities of the brewer and distiller, retailer, and distributor so as to prevent any one company from entirely controlling the industry. It also put control in the hands of the states, with the belief that states were most knowledgeable about how to regulate the alcohol industry to best meet their citizens needs.

But as consolidation continues to shape the industry, corporate brewers have begun to threaten the three-tier system by extending their reach beyond production and into distribution. For instance, ABI is increasingly using exclusive contracts with distributors to keep independent craft breweries off the shelves. While these contracts are optional, they provide lucrative bonuses to distributors that opt to partner with the corporate giant.

And a few giant retailers are rolling up control over sales. In Washington State in 2011, private retailers poured millions into a campaign to end the state’s control over liquor sales. Retailers argued that privatizing the spirits industry would lower prices and raise availability for consumers. Before the new laws were implemented in 2012, liquor was sold in just over 300 state-controlled stores. By 2014 that number had increased to around 1,400 independent retailers, pharmacies, wholesale buying clubs, and groceries. But it soon became clear that liquor prices were rising for consumers – by about 15% by 2015, largely due to distributors and retailers passing on fees meant to compensate the state for its lost tax revenue. Meanwhile, retailers have been the real winners, with Costco alone controlling about 10% of the state’s liquor sales by 2014.

These changes hurt almost all Americans. Independent brewers will find it harder to get to market and to scale up business without being bought by a multinational corporation. Consumers in smaller cities and towns will find it harder to find that special craft beer. And our post-Prohibition safeguards against monopoly control of the alcohol industry will continue to be threatened, challenging laws that have been implemented and protected by local governments for decades.

For an in-depth timeline of acquisitions in the beer sector, check out this timeline by VinePair.

Parts of this essay are excerpted from “A King of Beers?” a report by the Markets, Enterprise, and Resiliency Initiative (now the Open Markets Institute.)

Grains

From loaves of bread to processed snacks to animal feed, grains make up an enormous part of the American diet and agricultural economy. In 2011, sales of wheat, corn, sorghum, cotton, hay, rice, and oats accounted for over $135 billion of all agricultural output, nearly 95% of agricultural output by sales. Yet here too, control over this industry is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few giant corporations.

Read More

Corn is the most industrialized of all the grains. Corn comprises bout 40% of all grains, and 30% of all crops, grown in the United States. All that corn is used for livestock feed, ethanol production, and high fructose corn syrup. About 36% of the corn grown in the U.S is consumed by livestock, and around 40% goes to ethanol production. Most of the remaining crop is exported, with a small amount used for domestic food products, like high fructose corn syrup.

One of the main points of control over grain farmers is through seed DNA, as we detail on our GMOs and Seeds page. Food processing is also highly concentrated, with the number of major industrial bakeries reduced to three, as we detail on our Food Processing page.

But for farmers, the most immediate chokepoint most face when selling their grains is in the business of handling, storing, shipping, and trading grain. In the United States—and indeed around the world—these activities are now largely controlled by five companies: Archer-Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus (often called the ABCD's) as well as ascendant Cofco, a Chinese state-backed firm. The top 7 traders control roughly half of the global flow of grains and oilseeds.

These giants are also highly integrated vertically. In some regions of the country, they supply farmers with seeds, fertilizers, and agrochemicals, and then buy the resulting harvest to store in their own facilities. Then the companies might process that grain for use by their subsidiaries. They also have expanded beyond the grain and seed industries and into other agriculture sectors. For instance, Cargill operates several slaughterhouses and works in meat processing and distribution.

Despite historically high levels of concentration, grain traders have managed to roll up the industry further. In 1998 Cargill acquired the second-largest grain handler, Continental Grain, and in 2002 ADM acquired the majority of global trader Toepfer. In the years since, these giants periodically sell off lines of business to eachother and enter joint ventures. In 2015, for instance, Cargill acquired ADM’s chocolate business for $440 million and in 2014 ConAgra, CHS, and Cargill created a monopolistic milling venture, Ardent Mills. According to Food & Water Watch, Ardent Mills has “a stranglehold over most wheat farmers from the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi River.”

These companies are often privately owned, and famously private. It’s hard to know exactly how rich these companies are, and the breadth of their control, given that information about their finances often isn’t publicly available. In 1995, a Mother Jones profile of ADM CEO Dwayne Andreas marked one of the few media appearances of executives of that company. The profile discussed the importance of political savvy and passing legislation to the continued success of commodity companies, and pointed to intimate connections between the Andreas family and Bill Clinton, Bob Dole, and Richard Nixon as just a few examples of how private commodities traders are linked to the political process.

These four giants also have extensive trading operations on Wall Street and in the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which they use to buy and sell various forms of grain futures. Originally started as a way of guaranteeing farmers a fair price despite variable weather conditions, futures trading has become another arm of our national financial market. Traders speculate on the cost and price of grains to sell contracts for future harvests that may or may not exist. The trades happen at incredibly fast speeds, arbitrarily driving the prices of grains without much connection to actual supply and demand. During the 2000s, traders made over $250 billion in profits, capitalizing on emerging economies like China. This process is explained in greater detail on our Trading page.

The structure of government subsidy programs tends to promote further concentration in the business. Production of corn, like many other commodities, is subsidized through direct payments and crop insurance. While direct payments have a cap at $40,000 per farm, crop insurance has no upper limit. The Congressional Research Service estimates that crop insurance cost about $50 billion between 2000 and 2013. Crop insurance subsidies for corn totaled around $2.8 billion in 2013. Around 75% of federal subsidies go to 10% of farms.

Produce

Over the past 40 years, Americans have eaten more and more produce. Consumption of both fresh and processed fruits and vegetables reached 675 pounds per capita in 2009, an increase of more than 8% since 1976. In fresh produce alone, the growth was even greater: in 2009, the typical American ate 54% more fresh vegetables than in 1976, and 25% more fresh fruit. These gains are driven in part by increasing awareness of the health benefits of fruits and vegetables, as well as by policy that supports access to healthier food. Technological advances like cheaper transportation and better warehousing also have contributed to wider produce availability. But behind this encouraging tale, there’s a story of consolidation that is negatively impacting farmers, farm-workers, and the environment.

Read More

Middlemen—including retailers, railroads, and warehousing companies—have long played an important role in transporting produce from the field to the plate. But over the last generation, changes in antitrust policy have allowed many of these middlemen to consolidate vastly more power than ever before. The market share of the top four frozen fruit and vegetable manufacturers, for instance, grew from 27% to 41% between 1982 and 2007. The top five processed tomato firms controlled around 80% of that market in 2009. Walmart, the largest food retailer in the world, alone is responsible for about 15% of national produce sales. The implications of this concentrated market power are wide-ranging.

For farmers, consolidation in the manufacturing sector has made it more difficult to find competitive markets. Farmers hoping to sell their crops to processors or to wholesalers often have only one or two options in their region, making them susceptible to predatory contract relationships with those companies. As in other farm sectors, contract relationships generally favor the interests of the corporation. The percentage of vegetables grown under contract has grown steadily over the past two decades; in 2008, about 40% of all vegetables nationwide were grown under contract. Farmers have seen a steady decline in pay for their crops as consolidation as decreased the number of available buyers. Advocates and farmers have pressured chains like Whole Foods to purchase locally to offset some of their disruptive effect on produce markets, but the relative impact of these efforts is small.

Workers are also being affected by our increased reliance on imports, rather than domestic investment, to meet our national appetite for produce. Since the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1993, US consumption of imported fruits and vegetables has nearly doubled. The trade deal brought down prices for consumers, but carried consequences for our domestic industry. This rise in imports resulted in the shuttering of about 12% of California’s fruit and vegetable processing plants between 1992 and 2007. Fewer plants meant fewer jobs: between 1982 and 2007, the number of workers at California fruit and vegetable processing plants dropped from 27,000 to 18,000, a 33% decrease. And it also means fewer buyers for farmers’ crops.

Retailers, too, play a large role in dictating farmers’ income and consumers’ prices for produce. For instance, Walmart’s immense market share allows it to exercise enormous power over pricing and production. Whole agricultural markets rest upon Walmart’s contracts. Walmart’s emphasis on low prices squeezes its distributors, and in turn, the growers and farmworkers who fill those distributors’ orders. The real wages of workers in the fruit and vegetable manufacturing sector dropped by 32% between 1992 and 2007. Though consumers may see a lower price at the store, the costs of those savings are significant.

Large-scale produce growing in the United States was first realized with the rise of cultivation of farmland in California. In part facilitated by the sudden wealth of the gold rush, California saw rapid expansion of its agriculture industry throughout the mid- to late-1800s. Wealthy landholders held thousands and sometimes millions of acres of fertile farmland, which was used to grow grain for export in enormous quantities. At the turn of the century, a growing number of those landholders began subcontracting their land to specialty crop growers, often immigrants, many of whom specialized in fruit production. Those and other labor-intensive crops necessitated a seasonal source of cheap labor, with the result that California farmland was primed to be the site of racial and labor struggles in the coming decades. Today, California farmland is some of the most productive and intensively cultivated farmland in the country.

As the intensive, mono-cropping model first seen in California has made its way to other agricultural regions, farmers and consumers have started recognizing the negative impacts of industrial growing on the land and environment. Mono-cropping strips the soil of its nutrient balance, requiring additional inputs in the form of fertilizer and other chemical additives. Those chemical additives create a cycle of dependency, where farmers are reliant on chemical companies to ensure their crop yield. For more information on mono-cropping and the “pesticide treadmill,” see our page on GMOs & Seeds.