Organics

Once found mainly on the plates of California hippies and Vermont back-to-the-landers, organics are now a mainstay of many American diets. The fastest growing sector in the food industry, organics now account for some 4% of food revenues, and reached nearly $40 billion in sales in 2014. But as organic products have moved from niche to mainstream, big corporations have moved rapidly to capture more control over the business.

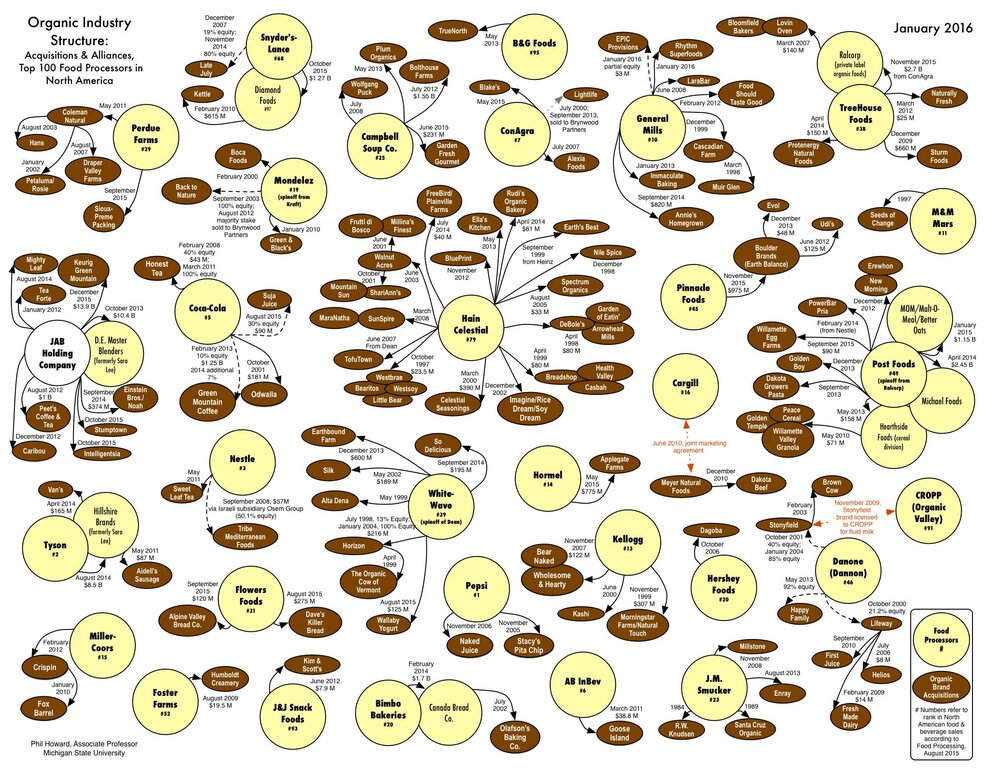

In recent years, a steady stream of mergers and acquisitions has concentrated control in the hands of just a few processors. Many brands that consumers believe to be mom-and-pop businesses are in fact now owned and managed by giant parents: Horizon Organic is owned by Dean Foods; Arrowhead Mills by the Hain Celestial Group; Stonyfield by Danone; Cascadian Farm by General Mills; Applegate by Hormel. Outside the most niche and expensive organic grocers it has become increasingly difficult for shoppers to find products from independent organic producers.

Read More

This chart, from Michigan State University’s Phil Howard, shows the extent of such concentration in the organic industry:

This concentration of power has also led to fear that the large companies will seek to erode organic standards. Congress passed the Organic Foods Production Act in 1990, calling for a federal standard for organics, and the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program (NOP) standards were implemented in 2002. On the surface, the requirements of the NOP seem very straightforward. To be certified as organic, produce must be grown without certain types of pesticides or genetically modified ingredients, and cannot be irradiated. Organic livestock, meanwhile, must be raised largely outdoors on 100% organic feed, and cannot be fed growth hormones or antibiotics.

But arguments about the fine print of the standards – especially concerning which additives organic farmers should be able to use – have persisted ever since, including a 2015 lawsuit over the process by which the USDA approves organic additives. Many farmers and consumer advocates believe the organic label doesn’t go far enough to ensure that organic producers actually uphold environmentally sustainable growing practices.

These concerns have intensified as larger-scale, corporate growers have begun to dominate the organic industry, displacing the small, independent growers that have long provided most organic products. Companies like General Mills, Dean Foods, Kellogg, and Kraft have become some of the most powerful voices in the organic industry. Some of these companies are represented on the board that decides what substances should comprise the National List, a list of non-organic items that can be added to organic products without losing the organic label.

And the power of these large companies is threatening to reshape the organic industry in other ways. Recently, there’s been controversy surrounding the proposal of an organic checkoff tax program, which would require organic farmers and retailers with gross revenue over $250,000 to pay into a national marketing and research fund. The program would ostensibly use those funds to promote organic products, and is supported by large organic processors. But given that many thousands of farmers believe their checkoffs represent the interests of the largest, most powerful companies in their sector, organic farmers and retailers are concerned that the organic tax program would be more of the same.

One of the largest obstacles to expanding organic production has been supporting conventional farmers in transitioning their land to organic. It takes three years to transition a farm to organic production, calculated from the last time a prohibited substance was applied to the soil. The transition process requires financial investment, and can be challenging for farmers with legacies of conventional or commodity farming. As a consequence, even the largest companies in the organic sector are having trouble keeping up with demand for their products. Attempting to enrich their supply chain, some organic companies are buying up cropland to grow their own crops.

Even the most conventional food companies are looking to organics for its market potential. Monsanto is getting into the organic game, using its technological advantage to cross breed, but not genetically modify, superior vegetables. The agrochemical giant is hoping to appeal to consumers who are squeamish about genetically engineered food, but can’t afford pricey organic produce. Monsanto has a leg up on smaller producers who use more traditional methods to select for the best crops. If their project is successful, the future of organic produce may move even further from its back-to-the-land roots.

GMOs & Seeds

The seed business is one of the most concentrated industries in American agriculture. Today, about 80% of corn and over 90% of soybeans grown in the U.S. feature Monsanto seed traits, either sold by Monsanto or by its licensees. In 2011, the top ten seed companies in the world totaled about $25 billion in sales, comprising 75% of the overall market. In 2020, the top four corporations, Bayer (formerly Monsanto), Corteva (formerly DuPont), Syngenta (part of ChemChina), and Limagrain together controlled 50% of the global seed market, with Bayer and Corteva alone claiming roughly 40%. And when it comes to genetic traits, this control is even more pronounced: Bayer controls 98% of trait markers for herbicide-resistant soybeans, and 79% of trait markers for herbicide-resistant corn.

Read More

Dominant seed corporations have built their market power over producers in several ways. For instance, corporations have designed many of their seeds to terminate—or, to fail to germinate—after one harvest, forcing farmers to purchase new seeds from them each season. Seed and agrichemical conglomerates also push sales of their products by designing them to work together. Bayer (formerly Monsanto) created its now famous Roundup Ready seed line intentionally designed to grow most optimally when treated with Monsanto’s Roundup pesticide. Roundup Ready products push farmers into a “pesticide treadmill,” in which they are dependent on both Bayer’s seeds and chemical inputs for a healthy crop. Additionally, Bayer-Monsanto simply bought many of its smaller seed and genetics rivals to further its control over genetic traits. Monsanto has even sued small, independent farmers who attempted to save Monsanto seeds from season to season, or who unknowingly cultivated Monsanto seeds after they blew over from a neighboring farm, for patent infringement.

As such, concentration in the seed sector is deeply tied to concentration in the agrochemical sector. The same four multinational corporations (Bayer-Monsanto, Syngenta, BASF, and DowDuPont) control 75% of plant breeding research, 60% of the commercial seed market, and 76% of global agrochemical sales. Accumulating power across both chemical and seed sales help these companies sell more of all of their products. Because these corporations are so dominant, farmers have few options when seeking alternatives to corporate agro-industrial giants.

The seed and agrochemical sectors shrunk considerably after two recent mega-mergers. Dow and Dupont announced plans to merge in 2015, completing the tie-up in 2017. Then in June of 2018, Bayer acquired Monsanto, creating the world’s largest seed and agrochemical corporation. A survey found that 84% of farmers are “very concerned” about the Bayer-Monsanto merger.

Another aspect of the dominance of these few corporations is their growing usage of Big Data. Monsanto, for instance, increasingly brands itself as a technology company, and defends its avid gathering of farm-level data as a boon for farmers, who will supposedly be able to use that data to better understand their planting and harvest schedules. But critics worry that this data could also be used to increase Monsanto’s knowledge of the relative performance of different farmers, hence its ability to discriminate in the prices it charges different farmers for the same seeds and chemicals.

The concentration of power in the seed and chemical business appears also to harm the environment in a variety of ways. Monocropping—which is when farmers plant a single type of plant cross an entire region—strips soil of its nutrients and increases the need for more agricultural inputs, such as fertilizers and pesticides. Those fertilizers and pesticides, in turn, find their way into groundwater, linger on supermarket produce, appear to harm the health of farm-workers, and have been implicated in the collapse of pollinator bee populations around the world.

Checkoff Programs

“Got Milk?,” “Pork: The Other White Meat,” “The Incredible Edible Egg,” “Beef: It’s What’s for Dinner” – in recent years these slogans have become staples of American advertising. What few citizens understand, however, is that these seemingly innocuous ad campaigns are part of a massive tax system that gathers some $700 million per year, and distributes that money to some of the most powerful business groups in food and farming. The programs that collect these taxes are known among farmers as “checkoff” programs. They require farmers to pay a certain percentage of their harvest into a national fund, which in theory is supposed to be used to promote the consumption of commodities like pork, beef, eggs, and milk. The current beef checkoff, for instance, requires ranchers to pay $1 per head of cattle into the fund. A board comprised of industry stakeholders then decides how to spend the funds.

Read More

The first checkoff tax program dates to 1966, and was used to promote the use of cotton. Since then, the USDA has approved 22 checkoff programs, including for beef and pork in 1985, watermelons in 1989, and mushrooms in 1990. In 1996, the Commodity Promotion, Research, and Information Act standardized the process by which checkoff programs are created and implemented.

These tax programs have long been controversial in the farming community. Many small farmers oppose mandatory checkoff taxes because they believe the funds disproportionately serve the interests of large-scale, corporate producers. As many sectors of the agricultural economy continue to be dominated by just a few powerful growers, small farmers are left paying into a fund that, in the case of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association for instance, spends much of its time lobbying for the political interests of giant corporations. And this issue isn’t just in the purview of conventional farming – many farmers also have objected to a recent proposal to launch an organic checkoff tax program.

Over the years, groups of farmers have tried to reform or eliminate the checkoffs. In 2000, during the last year of the Clinton Administration, more than 30,000 pork farmers voted 53% to 47% to end their checkoff program. Following that vote, then-Secretary of Agriculture Dan Glickman ordered an end to the pork checkoff. However, the National Pork Producers Council, which then managed the checkoff, challenged the results of the vote. In 2001, following the election of George W. Bush, Secretary of Agriculture Ann Venemen reinstated the program.

In August 2015, the Humane Society of the United States won a victory against the pork checkoff. A Washington D.C. federal court ruled that HSUS has could move forward with a lawsuit against the National Pork Board’s payment of $60 million per year in checkoff tax funds to the National Pork Producer’s Council, an industry trade group that lobbies for the interests of giant agricultural corporations. According to the court ruling, the plaintiffs now have standing to “allege that the Board used the purchase of the slogan as a means to cut a sweetheart deal with the Council to keep the Council in business and support its lobbying efforts.”

Parts of this essay are excerpted from “Got Organic?” by Leah Douglas, originally published in Slate.