States Try to Ban Surveillance Pricing in Grocery Stores and Beyond

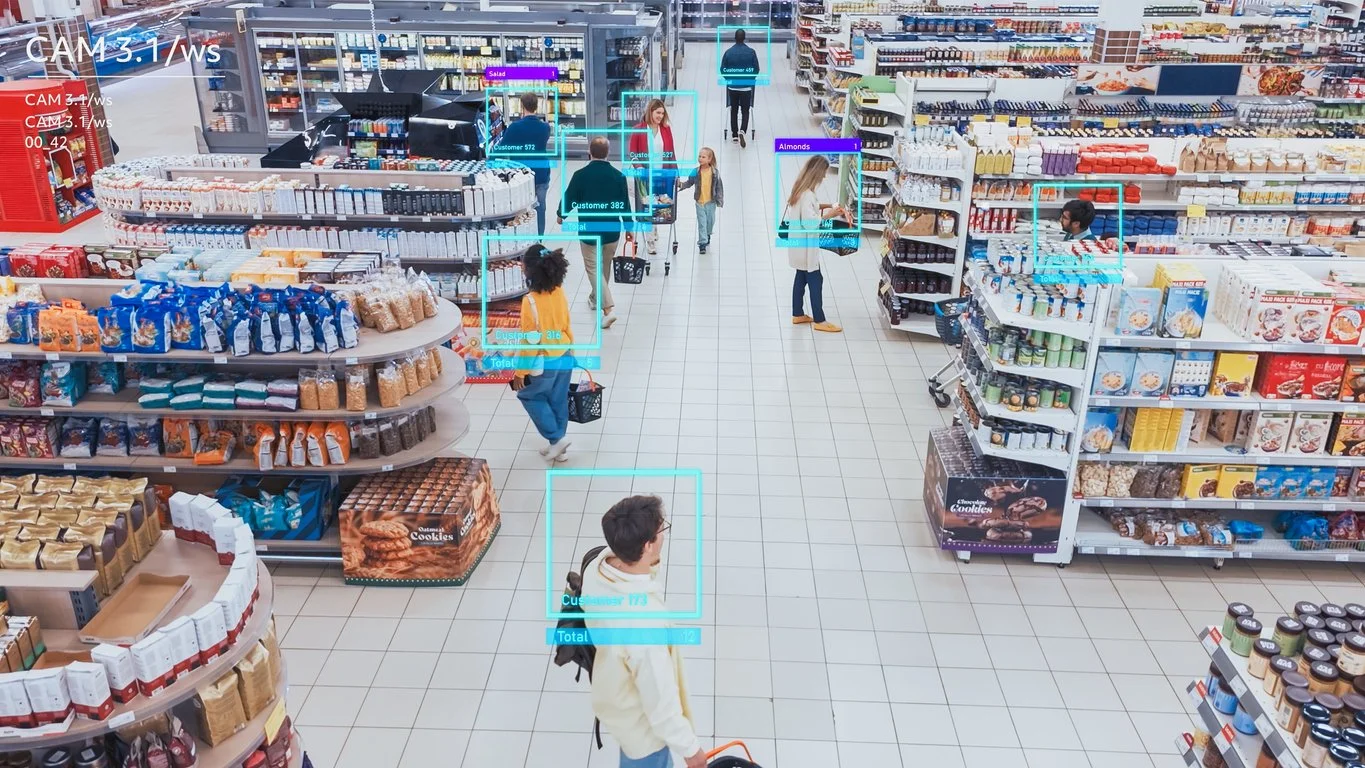

Are you paying more for pop tarts based on your web browsing history? Possibly. Grocery stores have many ways to show different customers different prices based on their personal data, including their mobile apps, online stores, and new in-store technology like smart carts and electronic shelf labels. Several states have introduced legislation to ban so-called “surveillance pricing.” But they could get thwarted by Congress, which jammed a 10-year moratorium on state-level AI regulations into its big budget reconciliation bill.

“We are in the middle of God knows what kind of tariffs, grocery prices are crazy high, and the idea of us getting screwed by an algorithm that realizes your bank account is low, that feels really scary to people,” says Katie Wells, director of research for the Groundwork Collaborative, a research and advocacy group that studies fair pricing policy.

Grocery chains collect and buy large swaths of data on customers’ location, past purchases, demographics, and web-browsing history to predict customer behaviors and offer targeted advertising, promotions, and prices. For example, big box store Target assigns customers a guest ID to track their demographics and shopping patterns in-store and online. These detailed profiles can predict things such as when a customer is pregnant (down to the rough due date). The question is, as that due date approaches, will Target charge parents-to-be more for infant essentials? Or, more likely, offer them a personalized “discount” that might not actually save them money? Right now, nothing is stopping them.

Many retailers have been caught offering discriminatory prices. Over a decade ago, an investigation found Staples charged online customers more for a stapler if they lived more than 20 miles away from a Staples competitor, i.e., if they had fewer options. In 2019, Target charged $72 more for a car seat on its app when shoppers were in or near the store, presumably because someone already at the store is more committed to buying something. Uber knows that users with low phone battery are more likely to accept surge pricing. Instacart introduced shopping carts with digital screens that display targeted ads and personalized coupons based on the shopper’s in-store location and purchasing history.

The highly opaque and dynamic nature of surveillance pricing is different from a special discount for seniors and veterans or a loyalty coupon for buying a lot of one brand. Advocates for surveillance pricing bans do not want to end all group discounts; they want the criteria for getting a discount to be made public and offered to everyone who is eligible. Otherwise, behind the shadow of an algorithm, grocers can offer inconsistent and exploitative deals that shoppers might reject as unfair if they were made public.

“The issue is often the transparency,” Wells says. “What feels unfair in this personalized data moment is that you have no idea why I’m getting a cheaper deal on the dog food, and you have no way to change it or figure it out.”

As pricing gets more private, shoppers will have a harder time comparing prices and discerning what is truly a deal. “The more individualized pricing expands across the marketplace, what exactly is a discount becomes very opaque,” says Nina DiSalvo, policy director for Towards Justice, a nonprofit impact litigation firm. “If me and my three friends all buy the same product, one pays $3, one pays $4, I pay $5, and the last person pays $6, did I get a discount?”

Grocery market consolidation amplifies these problems because it limits consumers’ ability to shop around. Even if someone knows that their personal price is not a good deal, they may not have another option. Allowing surveillance pricing could make grocery consolidation worse, because only the largest firms have the resources and data troves to use these practices and reap new profits.

Several states have introduced bills to ban or regulate surveillance pricing. New York state passed a requirement that any businesses using data-driven personalized prices must post the disclaimer: “This price was set by an algorithm using your personal data.” The Massachusetts Senate advanced a bill this week that would prevent grocers from charging different prices based on shoppers’ biometric data, like fingerprints, faceprints, or voice. California also advanced a bill out of committee last week that would prohibit retailers from “offering or setting a customized price for a good or service for a specific consumer or group of consumers, based, in whole or in part, on covered information collected through electronic surveillance technology.”

The California bill would still allow for discounts for members of groups, like teachers or seniors. It also allows for personalized prices offered through loyalty programs, which could provide grocers a major loophole.

Colorado, Georgia, and Illinois introduced similar surveillance pricing bans that go a step farther toward banning data-based personalized prices and wages.

On-demand delivery apps such as Uber, Instacart, and Shipt pay their gig workers based on an algorithm instead of miles driven, hours worked, or orders fulfilled. Gig workers have no way of knowing what factors determine their pay, and apps could use personal data to pay the minimum they’re willing to take, such as offering workers less during hours they typically work. Gig corporations use gamified, unpredictable pay, like bonuses for completing a certain number of deliveries within a certain time frame, to coerce workers to take lower-paying gigs or work certain hours.

Corporations like Uber can exploit their middleman position to set personalized prices for consumers and workers, charging consumers as much as they possibly can and paying workers as little as they possibly can to maximize profit. “Basically, you are seeing the company being able to retain any modicum of surplus that might exist in the transaction,” says DiSalvo.

There’s a case to be made that personalized pricing already violates consumer protection and anti-discrimination laws. However, collecting information about proprietary, black box algorithms is extremely challenging. Prices constantly change, and it is hard for shoppers or workers to know if, in any given transaction, someone, somewhere else, in that same moment, paid a different price or received a different wage. It is harder still to prove that that difference was based on a protected characteristic like race or gender.

State surveillance pricing bans face an unusual threat from Congress. In the latest sign of coziness between Big Tech and Washington, tech corporations have lobbied to block all state-level regulations on artificial intelligence (AI) for a decade, which would include bans on surveillance pricing. The federal moratorium passed out of the House Energy and Commerce committee’s budget reconciliation package and will go to the full House for a vote. If the budget passes the House, the moratorium could get struck down as extraneous legislation in the Senate.

What We’re Reading

As House Republicans propose massive cuts to federal food assistance, President Trump suggested reviving his first administration’s food box program. The program was widely criticized for fraud and abuse. (The Cocklebur)

The FTC’s Robinson-Patman case against Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits survived a motion to dismiss. (Bloomberg Law)

A new report commissioned by retail workers’ unions reveals the harms of understaffing and underinvestment in stores for shoppers and workers. One outcome of understaffing is price label errors. An investigation by Consumer Reports found that Kroger routinely fails to take down expired sales tags, leading shoppers to pay full price unexpectedly at checkout. Meanwhile, workers’ wages have stagnated, with 80% of surveyed grocery workers unable to pay for basic living costs. (Economic Roundtable, Forbes, and Consumer Reports)